A Reflection on Designing Place and Policy

Indonesia’s New Capital Project

RESEARCH | ACADEMIC

Jeamme Chia | Gioia Connell | Dewi Tan

published in Edge Effects

photo credit Jeamme Chia

“Keputusan pindah ibu kota bukan hanya pindah lokasi, bukan hanya pindah istana, bukan hanya pindah kementerian. Kita ingin pindah kultur kerja kita. Kita ingin membangunkan sebuah sistem sehingga ada kecepatan kita dalam memutuskan, merespond perancaman yang ada. Kita ingin membangun sebuah kultur, sistem kerja yang baik.”

"The decision to move the capital is not merely to relocate the Presidential Palace or ministries. We want to shift our work culture, to build a system where we can swiftly address and respond to threats”

— Indonesian President, Joko Widodo, 24th January 2020

In August 2019, Indonesian President Joko Widodo announced that the country will build a new capital city in East Kalimantan province on the island of Borneo.

The sheer scale of such a project is hard to imagine. The Indonesian government plans to transform 200,000 hectares of inland forest—almost three times the size of New York City—into the country’s new administrative headquarters. With a price tag of over $32.79 billion and a total of 1.5 million civil servants estimated to make the move from the current capital Jakarta to the as-of-yet unnamed city, the new capital is an ultimate exercise in planning and design.

The mammoth task is matched by monumental ambitions. Painting a compelling picture of one of the world’s most sustainable forest cities in a televised conference, Widodo outlined the importance of the move to the country, to Kalimantan, and to Jakarta. New capital plans promise to alleviate environmental and population pressures in Greater Jakarta, where 30 million people suffer from persistent problems of flooding, congestion, subsidence, and air pollution. The new capital also seeks to more evenly distribute development across the country, creating new centers of growth outside of Java. Ultimately, the new capital is a crowning commitment to Indonesian identity. By strategically shifting the center of power from its colonial port city to the geographical heart of the country, Indonesia seeks to solidify a self-determined national unity across its diverse archipelago. Creating this city is more than a civil infrastructure megaproject—it is a rewrite of national narrative in built form.

Relocating a national capital is not unprecedented. With the move, Indonesia will join over a dozen countries worldwide that have relocated their administrative centers since the mid century, including its Southeast Asian neighbors Malaysia and Myanmar. Yet these experiences offer poignant premonitions. Putrajaya’s green infrastructure is undermined by boiling hardscapes and energy intensive architecture. Brasilia’s beauty is shadowed by segregation and inequality. Yamoussoukro in Côte d'Ivoire has yet to grow as dynamic and thriving as the country’s former capital Abidjan. Is it possible for Indonesia’s new capital—its Ibu Kota Negara—to avoid these same fates?

This Piece is a Call — May the Pandemic Prove to be a Period of Inflection.

With COVID–19, this question is a timely one. The disease has effectively pressed pause on the new capital’s once fast-track construction plans. Similar to many countries around the world, the pandemic is also shining a bright light on long-standing disparities in Indonesia. Within cities, dense poor and informal settlements with little water or sanitation infrastructure have seen COVID cases skyrocket. Between cities and towns, unequal access to health services further reveal the need for extending basic healthcare across the country. Citizens are left to wonder how relocating the capital will be able to both alleviate environmental and social issues in Jakarta and avoid their recurrence in Kalimantan.

The pandemic has the potential to shift the physical bias of urban sustainability projects to those that more closely integrate with environmental and social systems. Across the world, it was common practice for countries and consultants to propose large scale architecture and infrastructure solutions as the answer to human wellbeing and environmental conservation. Now, with the tolls of inequality increasingly visible in traditional urban development, we are witnessing how it is the unseen—the underlying conditions and policies—that define resilience or the lack thereof.

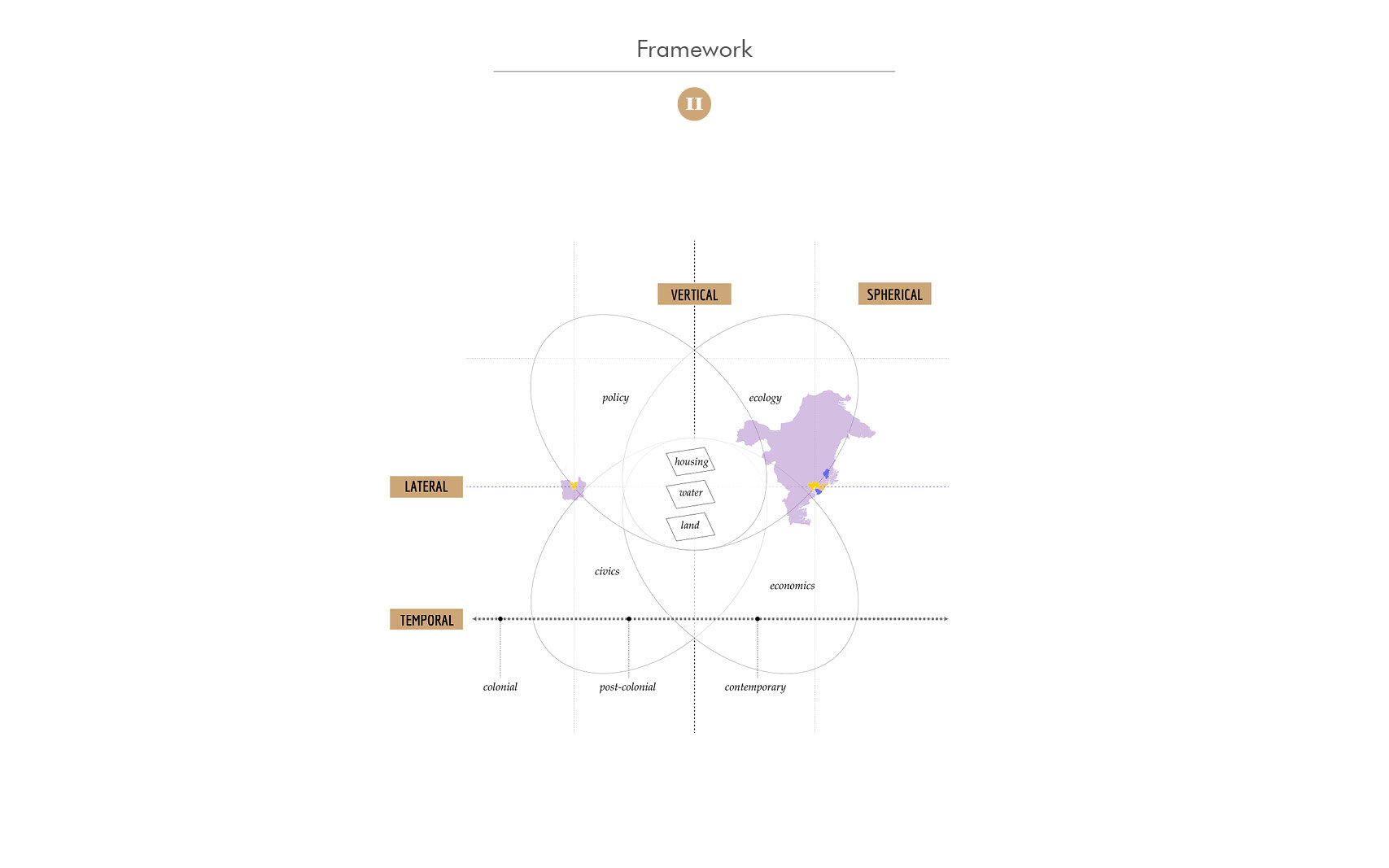

Revealing these dynamics as they apply vertically across layers of our environment—from housing and water infrastructure to land and forests—will be foundational to achieving climate resilience and equitable development in East Kalimantan, Jakarta, and Indonesia as a whole. This piece is a call—may the pandemic prove to be a period of inflection in which reading the landscape of lived experience, of policy, and of ecology define the process by which Indonesia undertakes its new capital project.